Spoiler warning

I’m not sure that I can say as much as I want to about ‘Love, Simon’. It came out last year and I’ve just got around to watching it. It is a romantic drama featuring, for near on the first time in mainstream Hollywood cinema, a gay protagonist. Simon is a closeted 17 year old whose life changes when he begins an email correspondence with a boy from his school (known only as ‘Blue’) who has spoken anonymously about being gay and closeted on the school’s Tumblr page. As they start regularly chatting to each other over Gmail, and falling in love, Simon is blackmailed – a strangely classic trope of gay tragedies – by another student. Simon tries to discover Blue’s identity. The film runs us through several candidates, before the two boys find each other in a heartwarming final scene that takes place on a ferris wheel. The end! The plot is simple, but it’s a great movie. I was touched by the film and was struck by its deftness of approach, its daring straightforwardness and a radicalism which caught me off guard; I’m still reflecting on the experience.

I felt that a part of me was represented on film for the first time; like many gay men who have been moved by this film, it was the representation I did not know I needed. And to see a non-stereotypical – as problematic as that is, and I want to talk about this at another time – young gay man shown being attracted to other men was strangely reassuring for someone who struggled with his sexuality in the past, even though I’ve been out for seven years and have seen a fair number of movies with LGBT themes. This is not an unusual reaction; but the film is more than a feel-good piece, or more properly: *through* being a feel-good piece it does more work than one might expect.

At various points in what follows I will be favourably comparing Love, Simon to Call me by Your Name (CMBYN). I think it is overrated, but I wouldn’t want to bash it for no reason. I would argue that that film falls down in ways, important ways, in which ‘Love, Simon’ triumphs. I don’t think this is an idle comparison; I think it allows us to see queer cinema more clearly. But YMMV. I certainly don’t think CMBYN’s reputation should be inflated by its arthouse genre box, and I do think some of the response to it has done that. But that’s another topic for another time, perhaps.

So… through being a feel-good film ”Love, Simon”, I think, ends up being really good. Take the montage of the first scene, accompanied by Simon’s narration, set spiritedly to the ‘Ooogum Boogum Song’. Simon explains that his life is both normal and privileged (if these can be run together!): the house in the suburbs, the loving and successful parents, the ‘sister he actually likes’. The contrastive punchline which follows is obvious. This opening monologue/montage has been criticised for its assimilationist message, “I’m just like you…”. But set against the power of the “except for…” which follows, as we see Simon receiving a new car, his parents cupping his eyes, and as we see him checking out the gardener across the street, I’m not sure the criticism has much force. The montage is bracing in a way which feels incredibly subversive. The lack of poverty or confounding factors acts to drive home Simon’s sexuality to the audience all the more forcefully. And the scene is bracingly funny and warm. I’m not sure I have ever seen a movie present a teenage boy desiring someone of his own gender presented with such charm, lightness of spirit and sense of play. One gets the sense that the film itself accepts Simon from the start; it is on his side, and so are we. The few seconds that it takes to make the articulation from ‘normal happy energetic teenager’ to ‘gay teenager’ have a bluntness that startles, a bluntness that more sombre queer films just do not have. To me, in comparison, their reticence seems like coyness.

The words “I’m gay” feature throughout the film. That simple declaration is actually surprisingly rare in mainstream cinema, but even more strangely, not always there in queer cinema either, and goodness did I appreciate it here. I particularly valued the lack of any reliance on sexual fluidity or a ‘love is love’ message, as in CMBYN veers into. As one commenter on a gay website posted, ‘CMBYN is about sexually fluid bros, ‘Love, Simon’ is about gay boys’. I think that’s right, and I think it is an essential difference. ‘Love, Simon’ does not focus meditatively or intellectually on gay identity, but nor does it have any interest in ignoring the centrality of identity – what same-sex attraction means for the subject in the world, for his or her self-perception, for how he or she relates to family, friends, and the cultural hooks which surround him or her. For too long gay cinema has found it chic to present same-sex love divorced from identity; I think it has also found it convenient. Queer films have indulged too often in wordless liaisons which momentarily puncture a normally straight life.

In reality, self-reflection will be a consequence of any unexpected same-sex liaison; the unreflective ‘love is love’ pansexuality of many queer movies is both unrealistic and unhelpful. Too many arthouse queer films – including the excellent recent ‘Never Steady, Never Still’ – see the silent depiction of moody spontaneous connections as a virtue. But in ‘Love, Simon’, Simon and Blue openly bond over sharing when they realised they were gay; they discuss being closeted and what it means for them; Simon fantasises about what life will be like in university, in a tongue in cheek sequence the campiness of which expresses, wryly, some real longing. The film lays it out. Forget less is more: more is more. The bane of queer presence in the mainstream is the circumlocutive drive – the moody wordlessness – and the analogical drive. We’ve certainly had enough of the latter! From opera dirges to science-fiction third gendered people, LGBT people have had to make do with – and in many cases have taken to producing – material which may have some kind of queer sensibility, boiled down to ‘it’s okay to be different’ much of the time, or other anodyne bottom lines. ‘Love, Simon’ is one of the few films to *unflinchingly*, without analogy – or apology – address an audience’s attention and emotions to the growth, to the adolescence, of a gay young man and the psychology of the closet.

And the film is particularly good at the psychology of the closet. Nick Robinson’s performance has been justly praised: we are alive to his moments of pain, his flashes of anxiety and forced self-control. His father’s mild homophobic joke when the family discusses the most recent episode of ‘The Bachelor’ is met with a convincing grimace; Simon’s yearning for connection, his sense of guardedness, are all displayed so very well. His sense of loneliness as he seeks out people who are ‘like him’ and candidates for being Blue, and his fear of losing himself, are conveyed with elegance. We are given “a deep, potent sense of who Simon is, what he needs, what he fears, and who he loves”.

This open expression of queer experience can sometimes take you off guard.

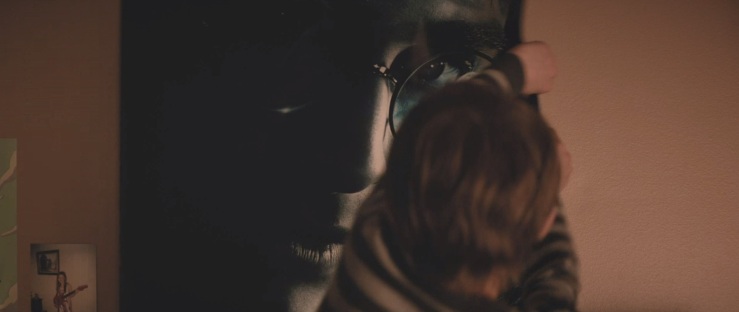

Upon rewatching some scenes I have been struck by how taboo-busting they really are. The flashback where Simon is telling Blue when he knew he was gay is one case: the unsettling images of a young boy waking up in distress, ‘for every night in a month’, thinking of Daniel Radcliffe, only to tear his poster of the actor down. We have seen countless expressions of heterosexuality from young boys in movies; but to see an explicit thinking back to homosexual desire, to see it manifested on the screen in the eyes of a child, is quite strange. It actually feels a little wrong to think of a boy of that age having gay thoughts. Why does that feel wrong, when I wouldn’t bat an eyelid at the straight equivalent? Why does it feel so refreshing to have that openly on screen? And yet here the film is revealing, again exposing experiences that countless queer people have lived through but which have never been represented in cinema. Simon tears the poster down. What is to most, a pleasure – the experience of attraction – is here pain and distress, a childhood nightmare. The film does not dwell on it – and it does not mourn it – but it deserves credit for its authentic and fresh representation of gay experience. And another taboo-buster: the scene at the ferris wheel where Simon discovers Blue’s identity for the first time, and they kiss. Seeing two kids of the same sex sit down next to each other, boys of the same build and age, obviously feeling attracted to each other, feels new and strange. It is a simple scene, and its pleasure is in the simplicity. Simon and Blue have an easy charisma. It is quite unlike the rapport between Elio and Oliver in CMBYN, upon whom that film tries to will sexual chemistry by force of languid cinematography, chemistry that materialises only weakly (the massive apparent age difference in that movie serves in my view to defang the queerness of their relationship; Elio’s attraction can be read as an intellectualised infatuation with an older mentor, something that might as well be straight – and indeed we never really know the sexual orientations of Elio and Oliver). By contrast: ‘Love, Simon’ is happy to put two teenage boys, two equals, on a ferris wheel car, let us feel the sizzle, and dares us to object.

Nick Robinson’s performance as Simon eclipses the portrayal of Elio. There is little interiority to the latter character; his eyes are blank, his behaviour – strangely in such an intellectual milieu – is rooted in instinct and reflex. This may be no fault of the actor, but as portrayed, Elio’s (seemingly unintended) glassiness and flippancy sabotages any sympathetic relationship. Contrast to the all-too-familiar stuttering when Simon says to his blackmailer “You’re gonna tell them.. tell them… I’m g…g…”; his irrational but perfectly judged flash of anger at his sister when she tries to support him; his flashes of happiness when reading Blue’s emails; or the perfectly pitched mixture of strain, anxiety and determination with which he comes out to his parents on Christmas Day. CMBYN, even when its lead character fails it, leans on the sumptuous, sybaritic richness of the Italian summer to provide *something* to the viewer. By contrast ‘Love, Simon’ leans on its lead’s performance to sell it, and remarkably for a subject such as this, it works.

Many critics have – in my view entirely correctly – been celebrating the fact that this film is a “mainstream” picture, recouping the tropes of American high-school movies and gaying them up, without making any attempt at ‘serious’ filmmaking. But critics often present this as if the movie is to be commended by virtue of the *effect* it will have – unlike Weekend, or CMBYN, the argument goes, it is a mainstream picture so it will reach mass audiences, including LGBTQ youth who may be inspired by it. This functional view is correct – so many queer people have been moved to come out by this film, or even moved to seek the love story that the dominant culture implied they could never look forward to; and the film has even persuaded some parents to view the struggles of their queer children with greater empathy. But the implication is that this does not pertain to the real merits of the film itself, that it is somehow outside of its merits as film. And I think that this undersells what ‘Love, Simon’ is doing. To their credit, some critics have recognised what they call the “magical ordinariness” and “subversiveness” of the film, a “revolution wrapped in candyfloss”. This does get some way to understanding the radicalism of the film, but perhaps not quite far enough.

‘Love, Simon’ is not just a high school movie; or rather it is not a high school movie with the palette swap from grey straightness to rainbow queerness. How could it be? The stakes are much higher; the movie knows this; we know it; the movie knows that we know it. It’s not ‘get the girl or not’; it’s a far more serious conflict. It is a love story, and a heartfelt one. But the conflict is not really about whether Simon does or does not get Blue, whether he ‘gets the guy’ at the end of the film. We live in a world where coming out (to oneself and others) is still surrounded with unarticulated anxieties and terrors that go to the heart of the human condition. The stakes are high and of a different quality; the audience knows this. The story beats and relationships are different as a result, including the contours of the love story. Some have complained that Simon and Blue do not show the kind of romantic connection that they should. But the point is that they connect over the closet, over their shared experience of homosexual desire. As in the real world, this is a powerful glue for queer teenagers. Each is the first person the other opens up to, and this thrill is the driver of their romantic connection: it also makes the romance sweeter, more tender, more inherently fragile and conditional.

We have never seen an on-screen high school romance that we can unironically support in the way we can with Simon and Blue. This partly explains why this is less a romantic comedy (as sometimes billed) and more a romantic drama – the similarities to ‘Mean Girls’ are thinner than one might expect, and this film just isn’t that funny. Any attempt to maintain the normal ironic distance with which a heterosexual pairing would be viewed in the classic teen movie collapses as the movie goes on and one becomes more and more invested in the success of the romantic hero. This is not just a gay version of the high school movie – I think this film has a different motor under the hood.

As I have mentioned above, the film strips away or softens the disadvantages you could imagine for a young man in Simon’s situation so that we can focus on the fact that he is gay. The film gives him – plausibly, for many children growing up in liberal parts of Europe and America – ambiguously progressive parents. Coming out is hard and emotionally fraught even with the kind of parents Simon has, as the film makes clear. But there are other things it strips away or defocusses, the better to connect us to the story. The film is, as critics have pointed out, PG-13 chaste. There are no peaches here. There is no sense of promiscuous gay life on the penumbra (as in Weekend), with some justification given the age of the main character. But there is still some sexiness, just of the more classic Hollywood variety, the suggestiveness of glamour and beauty and poised interacting figures. Had there been more than this, I don’t think the movie would have worked the way it does. The exclusion of earthier sexual longing creates a sweetness in its imagination of same-sex love and intimacy which is artificial, not naturalistic, but by this achieves the greatness that Hollywood artifice sometimes does.

The film is not without flaws. Towards the end, Simon is made to say a regrettably pat and disingenuous line about how, no matter who you are, revealing yourself to the world is ‘pretty scary’. There then follows a trite bit about how Simon’s coming out has inspired a new post on the school’s Tumblr feed, written by a girl ‘admitting’ that her parents don’t want her to become an actress and she feels unloved. You can almost hear the gears turning as the creators/studio heads try desperately to turn this very particular story into something with obviously universal relevance. The thing about stories of this kind is that they are universally affecting *by being particular*; the defensive turn the film makes here is unnecessary. The other point is that Simon is written as an ‘everyboy’, and that it sometimes feels that he lacks the individual quirks that would make the character feel more like a real person. When the film does give him interests, they are so studiedly masc – one response to the film criticised the too-deliberate nod to Radiohead – as to jolt you out of the world of the movie for a split-second. The film-makers seem to have been careful to ensure that no interest or attribute should accrue to Simon that the mainstream would object to. In my view, though, Robinson’s hugely affecting performance, driven by his own sense of who Simon is (the actor has said he played Simon as guarded and self-editing) does, mostly, overcome the script’s reluctance to pin him down.

This film is not complicated, though it is insightful, intelligent and touching. There are few layers of visual meaning to peel back and there is little ambiguity. And that should be okay! Some of the greatest films are simple. This is story about a romantic hero who slays a dragon and falls in love. While it is realistic when it has to be, like its genre stable-mates, it allows itself the indulgence of a dreamy world of good-looking people and curated bedrooms as a stage for its heroic arc. There is great power in films that harness such glamour, that use traditional film grammar *traditionally*, that forge a connection between the audience and the protagonist and take the audience on an emotional journey, seeing the hero overcome difficulty with bravery. And this particular journey has never been shown on screen before.